Trigger Warning: Discussion of death—animal and people.

My first impression of Jack was that he was an exceedingly calm puppy; my second impression was that he was a miniature version of my childhood dog—Homer—down to the white tip of his tail. That was fate enough for my mom and I.

We’re pet people—my family, I mean. While my dad’s love for pets is masked by that particular brand of strong renaissance man with a hammer, my mom is literally Snow White.

Growing up as an only child, I never wanted for a sibling. Why would I? We had pets. Three parakeets, three indoor cats, a sturdy outside dog whose barks I heard while cooking in my mom’s womb, and an innumerable amount of strays kept me company.

By the time Jack came along, my family was recovering from the passing of Homer—an awkwardly sized mutt whom my father named. He was my parents’ first dog together—an important distinction, as my mom always had a dog to baby long before my dad arrived on the scene.

I had experience with death by this point; I lost two grandparents in the fell swoop of a bad summer. I’d been to funerals. I’d seen bodies. I’d reckoned with mortality.

The passing of an animal is completely different. Pets, when they love you, love you. Unconditionally. Wholeheartedly. You are their world.

Homer’s passing, to my memory, seemed abrupt. My parents had shielded me from his condition until one night, it was time. We brought him in, lay his sturdy body on a blanket, and comforted him with pets and coaxes that it was okay.

I can’t recall the last time I sobbed like that, and I am an absolute crybaby.

As it turns out, I had only partially reckoned with mortality—I had gained but a sliver of understanding, of comfortability, with the end.

“I’m sorry, my stomach used to be stronger,” I murmured to my mom, gagging at the sight of blood on her finger from a fresh conure bite.

“That happens as you get older,” she replied as I tightened the bandage around the wound.

Jack was a Pekingese-poodle mix—so we were told. He was blond with bulging brown eyes, floppy ears with fur which naturally crimped when wet, a partially flattened snout, and an under-bite.

“And look,” said the man who had paid an unknown price for a dog without a true pedigree, “if you flip his ears back, they stay there.”

“Oh, wowww,” I remember my mom and I feigning, already enamored with him.

We were taking turns holding him; he was a sleepy-eyed pup paired with a high-energy miniature poodle with whom he was forced to compete over food.

The man giving him to us was a friend of my dad’s, prone to spending money on things he felt might bolster his status. He was experiencing buyer’s remorse, and we were the perfect trio to take one off his hands. (The poodle was adopted shortly after.)

Jack—who bore my mother’s name, which I swiftly changed—came home with us.

He was an interesting baby. Never a lapdog, he had a penchant for sitting atop the rocking chair and riding inside purses until he’d grown too large. His favorite toys were blue tennis balls found in three packs, which he would pop from his mouth in a reverse, semi-competitive game of fetch. He snored a lot. He enjoyed wearing sweaters. And he’d slept at the foot of my bed whenever I was sick.

Jack was my dog in the way that a kid’s first puppy was theirs; he was really my mom’s. A true Velcro-dog, she referred to him as “my blond shadow.” More than anyone, he loved my mom.

All animals love my mom; something in their animal instinct tips them off to the fact that she’s a spoiler. She’s everyone’s favorite—my wife and I’s dog included. Even the wild birds line the fence in wait when she steps outside, a fresh bag of seed bundled like a child in her arms.

Jack gave us some scares over the years, like the time he found a gap in the gate and happily trotted down the main road, only to be saved by my mom in her pajamas and a garbage truck functioning as her guard.

He was ever-curious and a protector, despite weighing all of fifteen pounds. He chased off groundhogs, possums, deer, and—had he been outside during its appearance—I’m pretty damn sure he would have barked at a bear.

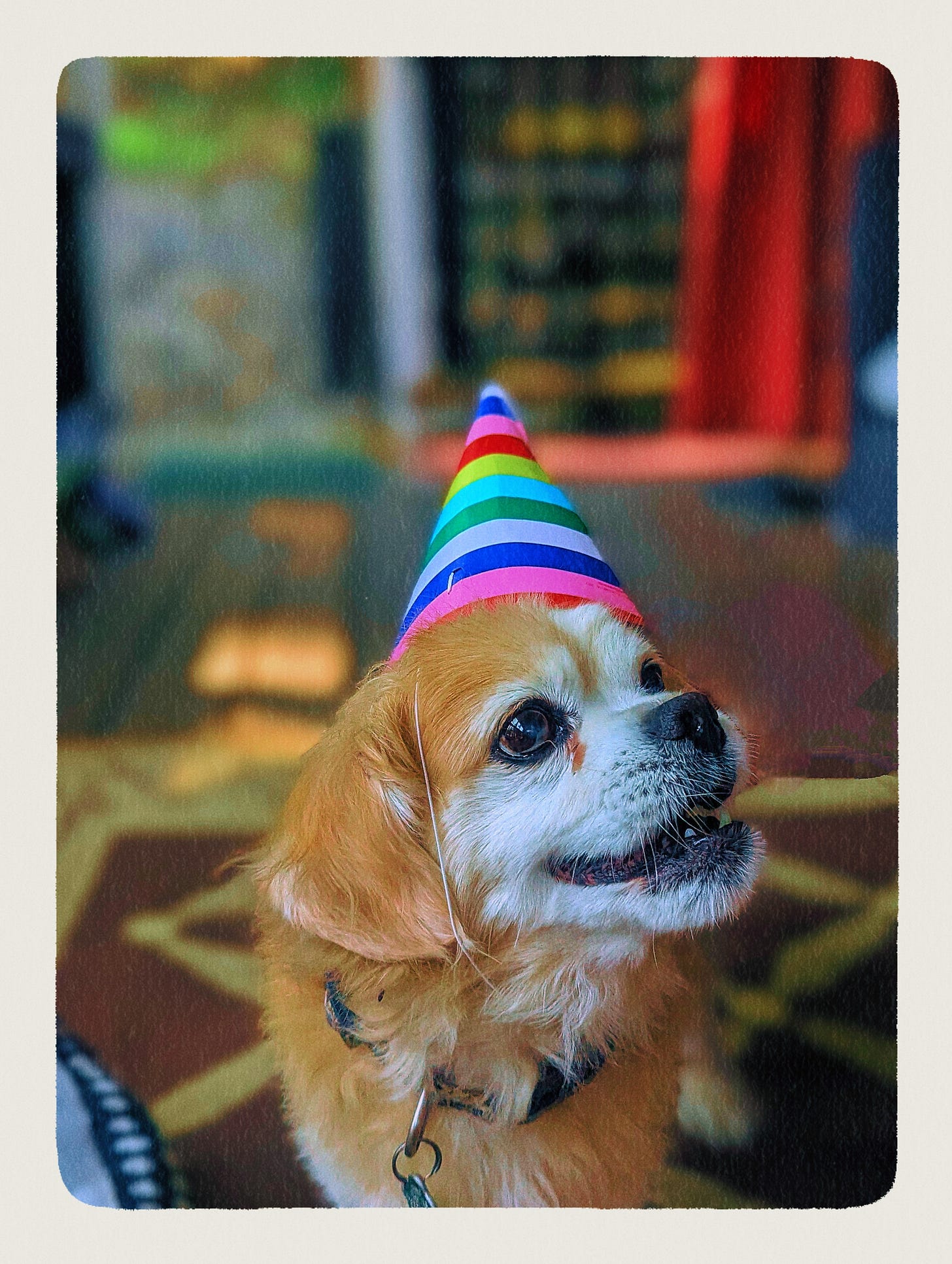

We taught him “sit,” “shake,” and “high-five.” He would greet me as arrived home from school and my dad from work. He liked to play the role of Blanket Monster—a beast which twists itself into soft blankets to growl and grump and roll about. He had a Glasglow-esque smile we referred to as his “J-J-J-Joker Face.”

When his hackles raised, the hair on his shoulders curled out in a manner that resembled angel wings.

Increasingly and especially during this holiday season, I feel surrounded by death.

Earlier this year, the last parakeet of my pair passed away a month or so after a surprise gender reveal by way of egg.

“No more birds,” I vowed, because parakeets simply don’t live long enough.

Two longtime library patrons passed as well—one, a man with numerous medical issues we often scheduled doctor appointments for, and the other, a former substitute teacher with a love for Harlequin romance novels.

Recently, while juggling the knowledge of incoming tyranny from our government, thoughts of Luigi Mangione, and figuring out how to get kids to read books, the son of the substitute teacher stopped in. I expressed condolences, and he made small talk by way of describing his mother’s tragic death in his arms. I didn’t know what to say.

Another: a former English teacher passed away, and her husband donated her collection of books. During the donation, he spoke warmly about her love of reading and of the tragedy that such a voracious reader was beset by dementia.

Every day, it seems, something is rotting.

On August 24th, Jack turned 15—officially making him my mom’s longest living dog.

Shortly thereafter, problems began. I will spare you the details of his decline; if you’ve ever had the privilege of owning a senior dog, you understand how grueling things can get, how many tears you can shed, how resilient and iron-stomached you can become.

Caring for an animal at the end of their life is a testament to the strength of the human spirit. You sit neatly between denying reality and an intuitive understanding that such things cannot perpetuate. You sacrifice comfortability to beg a reaper. Mortality stares you directly in the eyes and licks your face.

To love someone is to love their decay.

Jack passed away on November 19th.

I rushed home to comfort my mom, who’s experienced more grief than I can fathom and stands tall—all five feet of her.

I say goodbye to Jack, who lay in his favorite dog bed, eyes closed as if napping. I expect a snore. There’s none.

Grief is a funny thing; I couldn’t cry on the day, nor the following week, nor the subsequent month. I missed him through Thanksgiving, wishing to sneak a piece of dark meat to him while my dog was occupied with begging my dad. I missed picking out a new sweater for him to stay warm during the frost. I couldn’t cry, as much as I tortured myself with pictures of his big sad eyes and jutting teeth.

The numbness wore off the moment I caught myself calling for him, instinctively, as I stepped through my parents’ threshold. Despite becoming deaf in his last years, I never quite shook the habit of calling out to him and waiting for him to walk up, check my shoes for signs of animal contact, and accepting a loving rub on the forehead.

The tears were a relief, but now I find that grief comes in unpredictable spurts: dropping food on the floor, carrying in groceries, rounding certain corners.

When I come home for the holidays, I’ll stop at the door and wait for him.

Into that gentle night, I patter, tip, and tap, to nip your heels in dreams of follow-the-leader— I come cheek by jowl because I have loved you like a featherbed dog.