I’m putting this disclaimer at the top just to cover my ass: there is nothing wrong with wanting to associate your art with your birthplace. There’s nothing wrong with being from the region I’m from—I love my Appalachian folks! This is not a knock against you unless you engage in the heinous things described later. This is a critique of cultural aspects I take issue with, along with general griping about art and morals being conflated with the general attitude of the region.

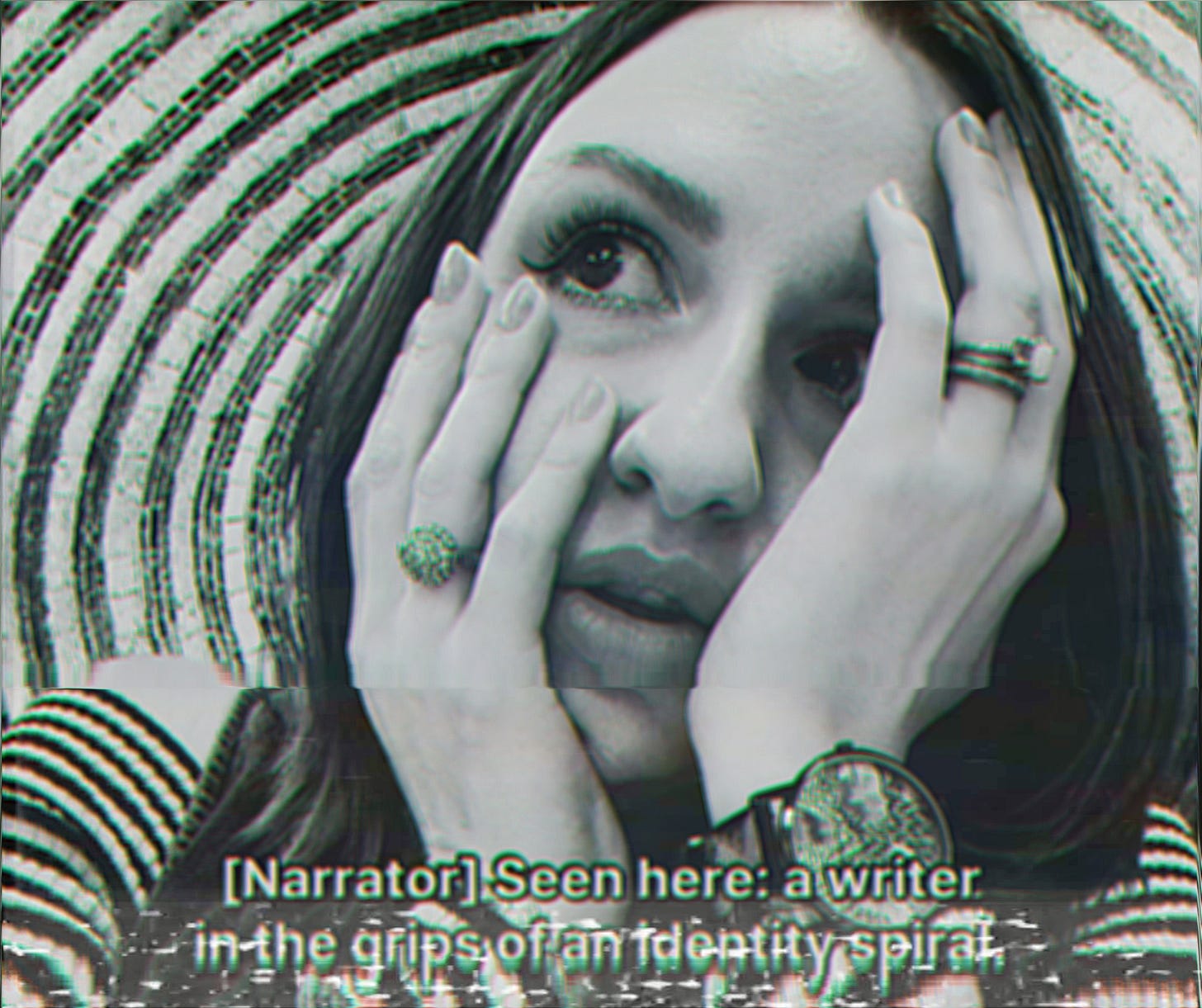

In short, this is a long personal essay about being caught between a rock (making a name for oneself) and hard place (being shackled by your physical parameters).

I am Appalachian. There is no changing this fact about me.

My proof is as follows:

I sound like gravy and biscuits when I’m angry or simply not paying attention to the way words fall from my mouth. I grew up making sawdust pies (my specialty) behind my grandmother’s house, climbing the mountainside with no regard for my safety. I was raised partially Baptist—as my grandparents were Baptists—which means hugging strangers and wishing them well isn’t too strange to me. I’ve been told that my hugs are very warm, and, admittedly, it’s a point of pride. I will hug a grandmotherly figure with the tightness of a grandchild, fully cognizant of how uncomfortable she would be if she knew I had a wife, not a husband. Nevertheless, she still deserves the warmth.

I have a burning desire to see my crumbling wreck of a hometown thrive the way I once heard it had back in my mother’s youth—as depicted in her extra-large cardboard sketches of downtown—and I can’t bear to part with it until I see the beginnings of a renewal. I am of the opinion that no one’s allowed to ridicule Appalachia unless they’re Appalachian. I’m staunchly pro-union, and I believe we lost great bargaining power when we stopped threatening to beat the Big Boss half-to-death in front of his wife and kids. I am ashamed my hometown has fallen victim to false idols currently on trial for throwing large sums of money he does not actually have at people to bury damaging stories. I pray for their de-radicalization.

Y’all is my preferred gender-neutral term. I love Mothman. I have pepperoni roll opinions.

I am a writer. There is no changing this fact about me.

My proof is as follows:

At a young age, my teachers commended my vocabulary and were very polite when I showed them the “book” I had written on quarter-folded notebook paper. I dictated short stories for my mother to type on the family computer. I crafted original characters with detailed backstories, character traits, and correlating pathos to date my favorite anime characters.

I finished my first novel—my bastard child Evaristus—at age 16 to impress an online friend. In high school, I entered a novella into a regional competition and snagged second place. I’ve birthed seven books total in the 100k word range—three of which are actually good!

I have the essential, base desire to write and create—which is all any writer needs to consider themselves a writer.

I am not an Appalachian Writer.

Says you.

“This is Erica, she’s a [state] writer.”

Haha, technically, sure.

“Hey, are you going to enter this contest? They’re asking for Appalachian stories. You’re a writer, so you’ve got a shot!”

I’ll think about it.

“Have you ever thought about writing about [famous local death]?”

I’m not equipped to cover that, no.

“So, this story is set in [state], right?”

No—wait, why do you think that?

“Sorry, while this is a very fine work, we’re looking for gritty, local perspectives.”

I mean, technically it fits those parameters, but I understand.

I’m not an Appalachian Writer. I do not claim this title foisted upon me, no matter how often it follows an introduction or accompanies conversation by implication. I hate when things are out of my control.

It’s been difficult to come to grips with the reality that people will form their own version of you—and it’s theirs, not yours. The frustration this causes is immeasurable, the thought of someone getting you wrong.

To live is to be a million different images, each dictated by time, place, and whose eyes are upon you. Narratives emerge, and, regularly, a single descriptor rises above to create You: The Monolith.

For me, that’s Erica: The Regional Writer.

Southern pride is a helluva drug, but I’ve always been straight-edge

Look, I know it’s gauche to bring up Stephen King—I’m not Stephen King; no one is Stephen King but Stephen King—but do you ever see the moniker “New England Author” set before “Horror Author”?

Perhaps that’s something you earn by being an icon and industry veteran, but I strain to think of a debut author described as “Debut, Region, Genre” rather than “Debut, Genre.” The “Stephen King only sets stories in Maine” joke comes secondary to his status of Horror Auteur.

Even local bands—aside from the “local” moniker—receive proper acknowledgment of their genre endeavors. I can’t remember a time where a shoegaze act was described as “Appalachian Shoegaze.”

For as much as I play around the genre spectrum, there’s an all-encompassing term for my work: “speculative.” This is a more truthful descriptor of the stories I create.

I am much more Rod Serling than I am James Still.

All this suggests that as long as your work isn’t region-specific—so long as you’re not marketing yourself as a regional artist—you’re golden. And I’m not marketing myself that way, so I should be fine.

“Please stop pointing me in the direction of regional imprints and agents; they’re not interested in my queer romances set in a vague location. They’re not interested in my queer horror that isn’t dripping with Appalachian-isms. They’re not interested in my speculative mysteries set in Hollywood,” I beg, only to be asked if I’ve considered writing about Appalachia just to get my foot in the door.

Circa 2018, I self-published a short story collection, which inadvertently set me back on the path of writing regularly and with some degree of discipline. I’ve posted two of those stories on this very Substack, including “The Trans-Allegheny Heretic.”

To date, it’s the closest I’ve come to writing “an Appalachian story,” hence the title. To date, it’s—ugh—my most-read, most-commented upon story. And that one’s on me! I put it first in the collection because it was my favorite. I love a story about female rage, what can I say? It’s my forte.

Back to the foot-in-the-door issue: I don’t want to go the disingenuous route. I’m not interested in writing about Appalachia. I live here. I have my own (gritty, local) perspective on it, but I don’t believe I have anything particularly interesting to say. It sucks sometimes, and sometimes the bad is interrupted by moments of beauty and community. This is universal; the same can be said about most places.

There is this underlying implication that, when writing about one’s hometown, it’s a nostalgia-driven piece that highlights the ugly without dulling the shine of its heart. “Criticize, but don’t complain: you’re lucky to hail from such a rich culture.”

Sure, I could write about foraging snake berries on my grandparents’ hillside, about the magic of cinderblock ovens behind the house, or about the leaking groundwater system forming a natural spring in their yard.

I could write about the way my baptism pushed me back into the closet for three more years, about how church sermons overstimulated my addled brain to the point of weekly sobbing sessions and hating myself to the point of craving death, or about the snide remarks and backhanded compliments whispered through paper-thin walls during Sunday school, as delivered by fifty-somethings with new grandkids about so-so’s shoes not matching her dress and isn’t her mother ashamed?

Maybe there’s something to Southern pride I never received the memo for.

Untangling Gnarled Roots

The manner in which you grow reflects in your personhood, and when you create art, it eeks into every crevice and lingers until you’re able to find and scrape out the proof. I squash my accent when it’s pointed out to me. I hate when things are out of my control.

I suppose it’s all in service to peel this label, even though I love others. I’m not shy about slapping the words “queer” and “writer” on my person; they denote pride.

And yes, this suggests that I am not proud to be a yeehaw-dy lady from the theoretical south. And yes, I think that’s a fair assumption to make about me. It’s more complicated than that, though. If you’ve grown up with negative media depictions of your locale, it affects your psychology.

I have a vivid memory of a school trip to Washington D.C., in which my still-best friend and I waited in line at a gas station. We were bundled in overpriced D.C. hoodies, snacks packed tightly in our arms, and we chatted idly about something I cannot remember.

Behind us in line was a man—gray, grandpa-ish—who interrupted our conversation about anime (probably) to make several attempts at placing our accents. I recall flushing with embarrassment when he got it right.

Now, I never readily admit where I’m from unless I’m blisteringly drunk and someone says my accent is cute. You gotta wheedle it out of me that way, and even then, I’ll hem and haw about whether or not you’ve even heard of it.

This suggests shame, a natural deterrent to spending more time than necessary dwelling on my surroundings, let alone the added effort of waxing lyrical about it.

And yet—oh, and yet—when my wife and I return home from a trip, my body relaxes when mountains spike high. It’s a fortress of unknown devils and soft-tailed deer that can kill you with stilled feet and a glance. A fortress of lush elegance or skeletal charm, depending on the time of year. A fortress haunted by the deaths of little boys and overworked men wrenching resources from it for the Big Boss’s pocket—

I want to punch the goddamn wall.

My ears perk at the mention of our name on the television, and I hold my breath for something neutral, nice, good. Most of the time, it’s just one of our politicians making an absolute ass of themselves. Occasionally, it’s a fluff piece about bikers raising money for children’s education that the system has failed to provide. Every once in a while, it’s something nice—no baggage or strings attached—but I am struggling to think of an example of something untainted by these complications.

In the span of three days, my friends can have a successful art pop-up in which the community shows up and shows out, and my wife can lose a non-tipping (🖕) customer because said customer discovered she’s married to another woman.

I love Appalachia. I am comforted by Her; I am terrified of Her. These feelings will remain until I’m rendered ash by way of cremation or a complicated geo-political war that decimates us.

On the other hand: I never doxxed myself to the good people of Habbo Hotel in my youth; I always told my myriad of husbands I hailed from L.A. or New York, which the television always depicted in glowing, somewhat unattainable lights.

The Future

The last legislative session in my area introduced several bills to restrict access to transgender healthcare, ban books, and do away with all manner of protections for vulnerable communities under the pretense of religion. Politicians here have never subscribed to the idea of “separation between church and state,” and their progressive adjacents have let them run wild without securing their own base to fight back.

Some months ago, I received a message from that still-best friend informing me that, should this Women’s Rights legislation go into effect, they’re out of here. The bill creates a narrow definition of “woman” as an excuse to strip rights from my trans sisters, to which I tell our lawmakers to go sit on something sharp.

I don’t blame my friend; with the prongs of defeat poking my back, I sat down with my wife to discuss the logistics of moving. But everything around us proved to be an albatross. I hate when things are out of my control.

It’s difficult to pick up and go when Appalachia is designed to keep the poor, poor. Mental health and social service workers are burnt out (I should know; I was one) and underpaid, and many programs ignore complicated solutions for quick bandaids and another name checked off the caseload. There’s an opioid epidemic ravaging generations both new and old, and the solution to “let ‘em dry out in jail for a few days” creates of domino effect of employment woes and a rinse-repeat.

Employment opportunities are bottlenecked to a few basic industries: healthcare, food service, or the mines. Healthcare, as the pandemic reminded us, is brutal on the lower rungs. In food service, you’re dehumanized by a majority of customers. If you’re a miner, rest assured you will be applying for black lung benefits before retirement age.

And god forbid, you’re a teacher.

No amount of bootstrapping can ensure escape; more often than not, it leads to being buried beneath a collapsed mine. The millionaire responsible will be slapped with a misdemeanor, then he’ll run for president as a Democrat.

These bills died in committee, which doesn’t preclude them from revision and eventually passing the House, the Senate, and being signed by the governor. The kicker? The trans-hostile language of Women’s Rights bill was not the deterrent—the clause to close a legal loophole allowing marital rape was a bridge too far for the Republican-controlled House.

And I must repeat thusly—

Appalachia is your grandmother telling you that you’re her favorite. Appalachia is knowing this is conditional, an honor to be won by flattening yourself into the shape of an open mountainside.

Appalachia is nostalgic stories of destitution, of sucking on sugar rags for dessert and laughing at the memory of picking your switch. Appalachia is recalling the sharp, accusatory words of your father—who will show the kindness he denied to you to his grandchildren—after his death and worrying that you’ve spent his lifetime trying to please a man who was backwards and toothless. (To which I say, “I will love you enough to overwrite that fear. I will understand you much easier than he ever could.”)

Appalachia is one step forward, three back, and one to right. Progress is hard-fought and ripped away by people cheering on Revelations and the Rapture, men who hate their families and insult them with jokes uttered at a fundraiser, and hefty megachurch donations nudging us back into nuclear idealism.

Appalachia has a spiteful type of kindness. I try to hold doors open, regardless. I make myself palpable in the ways that I can. I repeat a mantra, just to keep myself sane: the family I’ve built have grown from the same soil. But how could I despise a place where my favorite flowers have unfurled?

And yet I have found my spirit broken here more times than its been uplifted. I love her still, though her natural beauty has been broken just the same. They say enough pressure can turn coal into a diamond, and, well, my mouth is lined with 32 gleaming jewels.

I am not an Appalachian writer, but look where I’ve brought us: nearly 3,000 words spent on capturing Appalachia in a vain attempt to unravel my complicated feelings about regional identity. You sons of bitches: you got me. But this ain’t no hill for a climber—I’ve plenty of thoughts, and I hope some of them disquieted you. Take my words and don’t ask for anymore on this subject, unless we’re discussing change.

Here I sit, masking my accent when I can and cringing when my grandmother’s twang slips from my tongue. Here I sit, holding the “support local” slogan tight to my chest and demanding recognition from a desolate hometown.

I’m split between perception and reality, but self-identity remains king. My spirit remains entrenched in Appalachia, but my heart belongs to haunted city apartments, Underworld dimensions from the recesses of half-forgotten dreams, French-style kitchens on the strip frequented by demons, Drag King Nights starring the archangel Michael, country clubs ran by cultists, defaced dolls on the precipice of sentience, disgraced knights seeking companionship, and DIY basement shows with blood and fame on the line.

I am more than the parameters set by birthplace and timing; I am the visions I pen. So call me what I am: daughter, lover, writer, and feast.

An Ode to Appalachia

O’Appalachia—

you bastard.

You cooked me gray and said,

“Salt and pepper are enough. Anything extra

would be overkill.”

Then I braved the world,

tough to chew,

and prayed desperately to be savored.